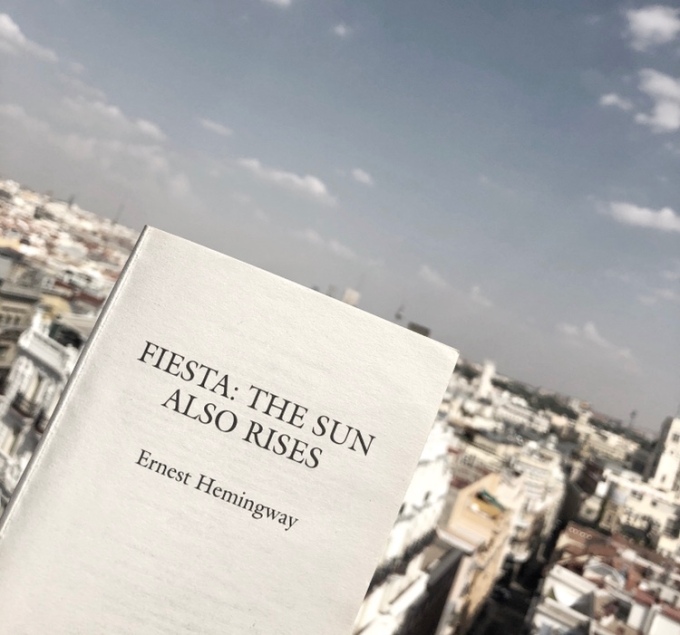

In September I travelled to the beautiful Spanish capital, Madrid, with my boyfriend to celebrate his 21st birthday. I thought there would be no better time to re-visit Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises, which takes the reader from Paris, to Burgette, to Pamplona, and finally, to Madrid. With all the construction taking place in the streets, it was hard to imagine the city as Hemingway saw (and adored) it, except on the rooftops (where we spent a good 1/3 of our time in Madrid). The city is beautiful and Hemingway’s Spanish novel is wonderful, although it does rack up some not-so-great reviews with phrases such as ‘macho crap’ and ‘sanctimonious jerkassery’ being thrown around, but maybe that’s a post for another day.

We didn’t eat at the Restaurant Botin, but it did make me feel all warm and tingly inside to think that it was at this restaurant that Jake Barnes utters one of my favourite lines ever written — ‘”Yes, […] isn’t it pretty to think so?”‘ — in the final pages of the novel. In the final scene of The Sun Also Rises, the taxi taking Jake and Brett from Botin’s turns out onto Gran Via. Hemingway writes,

‘”Oh, Jake,” Brett said, “we could have had such a damned good time together.”

Ahead was a mounted policeman in khaki directing traffic. He raised his baton. The car slowed suddenly pressing Brett against me.

“Yes.” I said. “Isn’t it pretty to think so?”‘

For one critic named Mark Spilka,

‘”Pretty” is a romantic word which means here “foolish to consider what could never have happened,” and not “what can’t happen now.” The signal for this interpretation comes from the policeman who directs traffic between Brett’s speech and Barnes’ reply. With his khaki clothes and his preventive baton, he stands for the war and the society which made it, for the force which stops the lover’s car […] As Barnes now sees, love itself is dead for their generation’.

Of course, Spilka makes a good point here, but it seems to me that his point is missing an important detail. If we are to accept the interpretation that ‘pretty’ means ‘foolish to consider what could never have happened’ because the policeman symbolises a society that will not allow for love, it seems important to note that the love that we are talking about here is romantic love. Spilka claims that ‘love itself is dead’ — and earlier in his essay, he claims that ‘only Hemingway seems to have caught’ the theme of the ‘death of love’, which he claims is ‘persistent’ in the literature of the 1920s ‘whole and delivered it in lasting fictional form’ — , but is love dead in this novel, or is there simply an absence of romantic love?

I’d like to argue that love is not dead in The Sun Also Rises, rather that love is at the very heart of Hemingway’s novel. Yes, there is no example of true and fulfilled romantic love in the novel — Cohn plays the part a chivalric hero whose absurd behaviour, according to Spilka, suggests that ‘romantic love is dead, that one of the great guiding codes of the past no longer operates’, and the love that exists between Jake and Brett is desperate and impossible — but this does not have to mean that love is altogether absent in the realm of the novel.

Much of Hemingway’s novel sees Jake Barnes, Bill Gorton, Lady Brett Ashley, Robert Cohn and Mike Campbell drinking, eating, arguing and commuting their way from Paris to Pamplona. This could easily be understood as a symptom of post-war life as there are flickers of such apparent aimlessness in much of the literature of the early 1920s — one of the many personas depicted in T.S. Eliot’s 1922 poem, ‘The Waste Land’, asks ‘What shall we do tomorrow? / What shall we ever do?’ and Daisy Buchanan of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s 1925 novel, The Great Gatsby deliriously asks ‘What’ll we do with ourselves this afternoon and the day after that, and the next thirty years?’. Such a reading of the wanderings and fiestas in Hemingway’s novel would agree with Spilka’s reading of The Sun Also Rises: there is no aim and no feeling in the novel because of The Great War and the society that it bred. Once again, this is a valid response to the novel, but, to me at least, it isn’t a satisfying one. As I re-read The Sun Also Rises, a quote by a critic named Donald Gastwirth came to mind. Gastwirth writes that, ultimately, what is do is meaningless; ‘it is only through the honesty and style with which we perform the action that we imbue it with meaning’. The actions of Hemingway’s characters may be, ultimately, meaningless, but the way that they perform them is not. In fact, I would argue that it is in ‘the honesty and style’ of the way that actions are performed in The Sun Also Rises, where both the true meaning of the novel, and the love that hides within it, lies.

In 1966, critic, Stanley Edgar Hyman, wrote that in The Sun Also Rises, life consists solely of ritual: ‘In addition to the organized rituals of the bullfight and the fiesta, drinking, eating, fishing, even playing bridge are made ceremonial and numinous’. The ‘organised rituals’ in the text are the formal events of the novel; they are the plot. Jake and his friends travel from Paris to Pamplona to watch the bullfights and experience the fiesta there. They drink in bars and eat in between drinking sessions, stopping on the way to Pamplona to fish and play bridge and if we look to these ceremonial and ritualistic actions, yes, it seems that the characters do wander aimlessly and that these actions are automatic, mechanical and unfeeling. But what Hyman fails to note is the moments in between the rituals. There are, as Hyman suggests, ‘ceremonial and numinous’ acts of violence, for example, in the shape of the organised bullfights, in The Sun Also Rises, but there are instances of hasty, reckless and emotional violence too — a fight breaks out between Jake and Cohn:

‘I swung at him and he ducked. I saw his face duck sideways in the light. He hit me and I sat down on the pavement. As I started to get on my feet he hit me twice. I went down backward under a table. I tried to get up and hit him. Mike helped me up. Someone poured a carafe of water on my head. Mike had an arm around me, and I found I was sitting on a chair. Mike was pulling at my ears.

“I say, you were cold,” Mike said.’

Likewise, there are definitely moments of ceremonial, ritualistic drinking in the novel, one example being the passing around of the Basque leather wine-bag while Jake and Bill are on the road to Burgette. ‘There is far more to the passing and drinking of wine than its mere consumption’, critic David Andersen notes, ‘the reciprocity begins to establish connections and alliances much as language would’; this ritual of shared drinking then gets passed to Harris when Jake and Bill reach Burgette and Jake, later in the novel, buys his own wine-bag and continues the ritual, passing the bag round during the fiesta. But although these are the most notable episodes of alcohol consumption that take place in the novel, there are other instances that stand out as being something else, something that isn’t celebratory or reverent. When Jake and Brett visit Botin’s, the reader knows that the novel is coming to a close. There is only a page or two of the book that he or she is holding in his or her hands left before the novel will end. Brett has written to Jake asking him to meet her in Madrid and Jake goes to her. The two are in love and this is their final meeting before the book will finish but despite their love for one another, they can never be together, and so the reader can only expect a sorry, tender closure to the novel. What the reader receives while he or she gets closer and closer to the novel’s final passage, however, is something oddly, discordantly close to much of what they have been witness to throughout the novel. Jake says,

‘”Let’s have another bottle of rioja alta.”

“It’s very good.”

“You haven’t drunk much of it,” I said.

“I have. You haven’t seen.”

“Let’s get two bottles,” I said. The bottles came. I poured a little in my glass, then a glass for Brett, then filled my glass. We touched glasses.

“Bung-o!” Brett said. I drank my glass and poured out another. Brett put her hand on my arm.’

Hemingway continues,

‘”Don’t get drunk, Jake,” she said. “You don’t have to.”

“How do you know?”

“Don’t,” she said. “You’ll be all right.”‘

“I”m not getting drunk,” I said. “I’m just drinking a little wine. I like to drink wine.”

“Don’t get drunk,” she said. “Jake, don’t get drunk.”

The way that Jake drinks, here, is much like the way that he, and everyone else in the novel, drinks throughout, but in this moment, it is not fitting; ceremonial drinking just doesn’t work in such an intimate space. Jake’s drinking, here, is desperate rather than ceremonial, greedy rather than numinous. The instances of violence and drinking that are not ritualistic are the instances that are ‘imbued with meaning’; it is not the action in and of itself that is meaningful, but the action in context and the way that it is preformed. A bullfight is a bullfight and drinking is drinking, but Cohn’s violent outbreak and Jake’s rapaciousness are much more meaningful, they are indicative of insecurity, guilt, and a desperate fear of intimacy.

Hyman does not mention romantic love in his list of ritualistic actions that he notes in The Sun Also Rises, but it seems to me that it does belong there. Like violence and drinking, love can be ceremonial. Cohn, after leaving Princeton, ‘was married by the first girl who was nice to him’ and ‘just when he had made up his mind to leave his wife she left him and went off with a miniature-painter’ and, of course, Lady Brett Ashley is engaged to Mike Campbell and is in the process of divorcing her second husband. Marriage, despite the fact that it is often a failure in the realm of the novel, is ritualistic, institutionalised romantic love. Like violence and drinking, however, love also exists outside of that which is ceremonial and ritualistic, although, admittedly, it is barely detectable. The kind of love that exists in The Sun Also Rises, that breathes gently through the pages of Hemingway’s novel, is an empathetic love. When Jake meets the Count for the first time, Brett tells Jake, ‘”I told you he was one of us. Didn’t I?”‘. The Count fought in seven wars and four revolutions, Jake suffered a life-altering injury during The Great War, Brett served as a V.A.D during the war, Mike and Bill also fought for their country — only Robert Cohn didn’t serve. The group, with the obvious exception of Cohn, share an experience, a horrible and traumatising experience, and this unites them; anyone who has suffered as a consequence of the war is ‘one of them’. Empathy is noted in the Oxford English Dictionary to be ‘the ability to understand and share the feelings of another’ and empathy for the situation of each of these characters cannot truly be felt unless one has experienced a war. They can all empathise with one another’s present situation, each of the characters wounded, rendered impotent in some sense of the word, scarred and somewhat numbed. Empathy in The Sun Also Rises is as Cassandra Falke considers it; not an act, but a ‘fundamental human condition’. Falke discusses the importance of empathetic moments:

‘The togetherness of an empathetic moment, such as sharing a smile, differentiates it from a moment of perceiving an object. Togetherness, in this case, does not mean simply a temporal-spatial coincidence, as in “here we are in this room together”, but suggests a condition of possibility’.

The Sun Also Rises contains such empathetic moments. When Jake and Bill go fishing together at Burguete, they eat chicken, hard-boiled eggs and drink wine for lunch. Bill

‘gesture[s] with the drumstick in one hand and the bottle of wine in the other. “Let us rejoice in our blessings. Let us utilize the fowls of the air. Let us utilize the produce of the vine. Will you utilize a little, brother?”‘

The two are fishing, eating lunch and drinking wine in Burguete. Hemingway describes the beautiful scenery when Jake wakes up early to dig for worms; it is beautiful, but it is only in this moment that it belongs to Jake and Bill. They are together and they share the scenery in this moment. It’s subtle and it may seem unimportant, but moments like these, small empathetic moments, moments of togetherness are moments of something unspoken, of a quiet understanding and a shared compassion and comprehension are moments in which lies love in The Sun Also Rises. Something similar happens at the end of the novel, after Jake and Brett have eaten at Botin’s. The two get into a taxi:

‘The driver started up the street. I settled back. Brett moved close to me. We sat close against each other. I put my arm around her and she rested against me comfortably. It was very hot and bright, and the houses looked sharply white. We turned out onto the Gran Via.’

The taxi is moving through the streets of Madrid and inside the car are Jake and Brett, still, resting, close and tragically in love. The small, subtle movements — Brett sliding closer to Jake, Jake putting his arm around her, and Brett relaxing into his chest — are empathetic; the world moves around them as the taxi drives past restaurants and houses, but all is still in the car and the small gestures, the movements that occur quietly and without grandeur are shared; they belong to, and are solely between, Jake and Brett. They are together in this empathetic moment. Falke writes of moments such as these: ‘This kind of empathetic engagement is not the only form of love […] but it is an important one’ and in The Sun Also Rises it is incredibly important. Once again, I turn to Gastwirth’s conviction that what we do is meaningless, that is the way in which we perform the action that we ‘imbue it with meaning’. When Bill raises his drumstick and bottle of wine to Jake, and when Brett and Jake slowly move closer to one another in the taxi, they, ostensibly, preform meaningless actions. It is only when we look at them more closely that they become meaningful. When the scenery is beautiful and two friends eat and drink together, and when the world is passing by and two lovers sit, still and close in the car, there is an empathetic moment, and there is love.

There may not be any example of romantic love in The Sun Also Rises, but there is not a complete lack of love in the novel. There is love, and it is empathetic. It is quiet, it’s a shared experience and a sense of togetherness and understanding; it sings through the heady red wine and the dancing at San Fermín, the fiesta at Pamplona.